Journalists want to show you nothing short of the most breathtaking, violent moments in conflict. Things that don’t make a coherent, interesting story should not make the cut in newspapers, magazines, and online articles. In Joe Sacco’s Palestine, Sacco destroys these norms of journalism by documenting every detail of his journey in Palestine using his unique graphic novel format.

In most articles, images are used to stimulate emotions in the reader, not to really contribute to the story.

Time described the death of an infant on the West Bank in 2014. They share an image that reflects the clashes occurring, but it adds nothing to the story:

Joe Sacco, on the other hand, uses the graphic novel to tell the story with a combination of words and images. As a journalist, he takes photos in a similar scene to the one above, but places them in succession and narrates the scene with small snippets of text:

He articulates that a single image cannot honestly describe a scene on its own, and neither can a full body of text with no images.

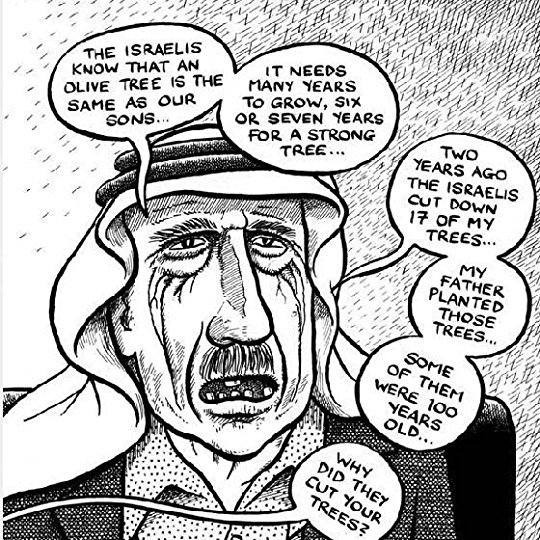

Where online journalism only captures the moments of highest violence, Sacco’s graphic novel captures people behind those moments. The long story format of Sacco’s novel to follow his journey all the way through Palestine offers stories that a single article would never highlight. The destruction of a field of olive trees does not seem like an emotional, story-worthy subject, but Sacco turns it into one by capturing his full conversation with a man who experienced it.

The successive word bubbles illustrate the emotional bursts of speech that come out of the man’s mouth. Deep lines on his face help to emphasize his suffering. Violence may hold a reader’s attention longer, but Sacco realizes that the lives of people behind the front lines are what matter most.

However, Sacco’s novel easily loses its place in the real world when compared with actual photographs. The cartoon drawing style that comes with a graphic novel format vastly differentiates Sacco’s work from the traditional works of photojournalism which accurately portray their subjects through photography. As a cartoonist, Sacco portrays his subjects in a caricatured manner, as can be seen on page 20 during an anti-settlement protest:

The exaggeration of the protester’s facial features, such as their oversized teeth, thick lips, and bulging eyes reflects more of Sacco’s comical and cartoony style than it does his reporting style. As a result, this leaves the reader with a more comical impression than it does a serious one, which reduces the overall gravity of his journalism. This aspect of Sacco’s journalism draws away from its authenticity and fidelity similar to how a caricatured drawing fails to preserve the reality of its subject’s appearance. Unlike most works of photojournalism which portray the Israel - Palestine conflict with severity, Palestine seems to provide a unique, comical visual perspective on the conflict through Sacco’s drawing style.

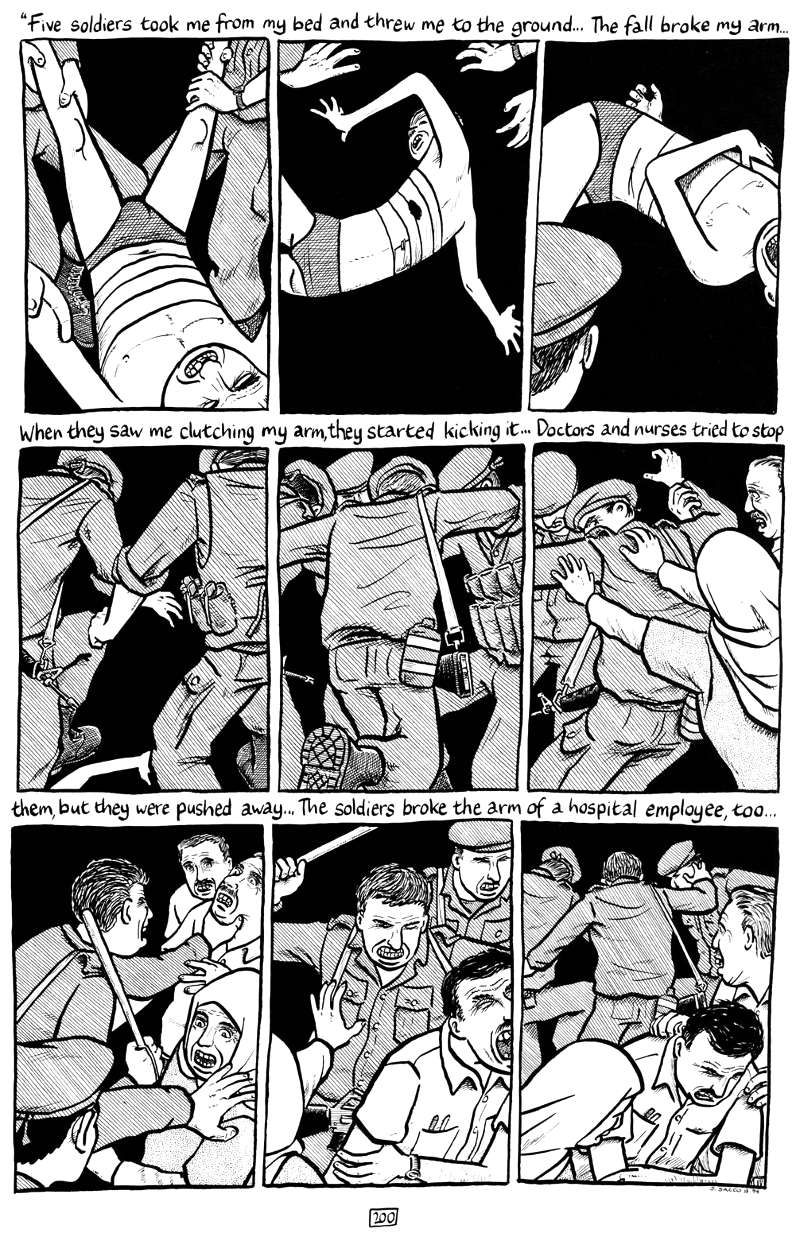

On the other hand, Sacco’s drawing style does not prevent him from managing to capture the brutal nature of the conflict in Palestine. During Firas’ story of being shot during his time on the Popular Front, he describes how he was beaten in the hospital by soldiers, and Sacco effectively depicts this violence:

In contrast to his depiction of the anti-settlement protesters, Sacco does not caricaturize the characters present in these panels. Instead, he emphasizes the brutality of the soldiers, illustrating how they mercilessly beat an already-wounded child and harming hospital employees. It seems that Sacco erratically chooses his drawing style for the scenes he illustrates, switching between a comical and a serious style.

In fact, when asked about his drawing style during

an interview about Palestine, Sacco replied, “When I started drawing the Palestine comics, everything I drew was very cartoony; everything was exaggerated. That was the only way I knew how to draw. At some point I realized, this is serious material, I need to be as representational as I can be, which isn’t that great, but I just sort of left my own character behind.” Clearly, this struggle between needing to be comical and needing to be authentic is evident in the unpredictable drawing style of Palestine.

In Palestine Joe Sacco’s unique use of short phrases of journalistic content creates a full story that is both entertaining and enlightening. Throughout the novel, Sacco writes, in text boxes, many different observations that he notices of each scene and scenario. This use of note-taking shows information to the reader that might be difficult to perceive without having been in the actual scene.

This page details a peaceful march in East Jerusalem. The block text boxes give extra information in short bursts that depict the importance of such an event. Because the boxes are short, they give critical information about the march that triggers an emotional response from the reader. This type of box is found all-throughout the novel. The text boxes show retell to the reader, from a someone with first hand recollection, what it was like to be there at the time.

Despite the caricatured style of Sacco and the people around him in his graphic novel, he remains very faithful to the unbiased story. Pictures describe what is truly happening in the scene, not simply what is the most extreme capture of a group of photos. Text is placed in such a way that it articulates its proper sequence, but also portrays the emotions of people he interviews and encounters. In this way, Sacco is able to describe the full picture of the situation in Palestine to his, and to anyone’s best ability.